My first three masks finished

Well if someone told me a few years ago that after all the time/effort/money of art school I'd be making paper mache' and hot-glueing felt to masks for a show, I'd probably have socked them in the stomach, and I'm not a very violent person. But for this show (

for more info on what this show is read this fecalface.com blog post), crafting just makes sense, its cheap, fast, fun, and effective. For the main focus of our show in Mexico at the end of Feb, Alan Pheiffer (the artist I'm working with out of Mexico City) and I decided to explore the tradition of mask-making, asking people to think about their own idols, fears, oppressors, and possibly people they feel the need to imitate or mock...even if its themselves. We hope to get outside of the usual roles of artist/curator/gallery and open the show up to new communities.

Bernal, Mexico

To explain a bit on how it all came about... while in Mexico last fall, Alan brought me to a mask museum in the town of Bernal

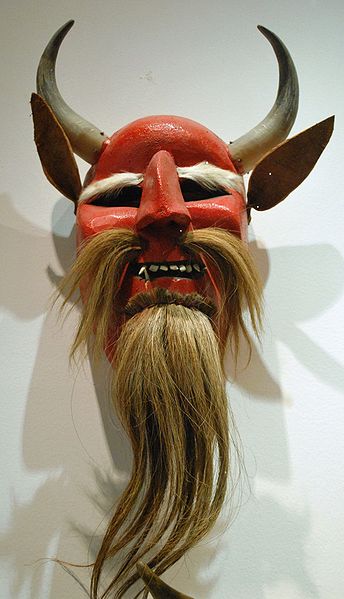

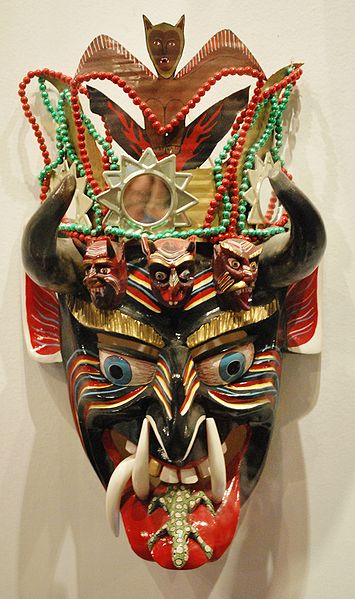

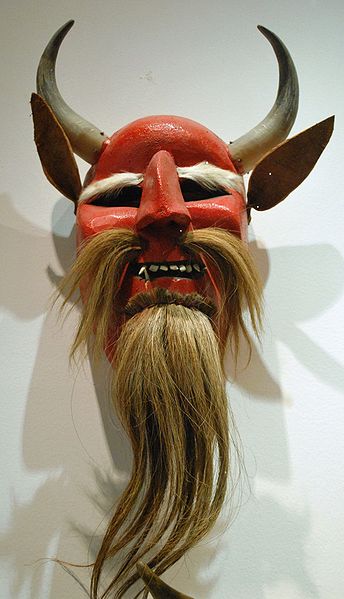

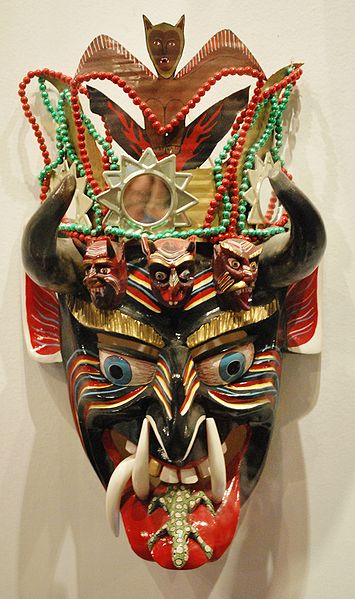

Inside the Mask Museum, Bernal

Mask Museum, Bernal

He explained to me some of the history of masks in Mexico. He explained how many indigenous Mexicans would use masks in their festivals to mock their European oppressors. We discussed the importance of these sort of rituals, not only in Mexico, but throughout history world-wide. We decided to focus our show on bridging our own artistic communities with the communities around Tequisquiapan Mexico. Alan and I are asking friends and colleagues to create their own masks to add to a collection, which we will then take on the road to villages in the Queretero state of Mexico. We will display these masks in public squares and ask locals to add to the visual dialogue by making their own masks. The entire collection will then be shown together at the end of February. If you would like to participate by making a mask, please contact me asap for details on artist' commissions as well as some possible mask making parties in the next couple of weeks. I will be bringing as many masks as I possibly can down with me to Mexico. If you are out of the Bay Area and unable to pass your mask on to me, still contact me if you want to be a part of the show, we can work out a way for your mask to make it. I will be updating a

facebook page for the show as well, called Más Cara, and hopefully participants will post photos of their masks in the works. I'll leave you with several amazing masks that Alan has passed on to me from his searches for Mexican masks online, as well as some text he wrote to help inspire and educate folks. Thanks Alan!

Mexico is a country of masks, a country full of fear from revealing itself, fearful of being exposed to the outside; but the world is also a world of masks: Everyone is impersonating one or more different characters, protecting themselves from the hostile surroundings, from society, from the known tyranny of living just once. Vargas Llosa, the peruvian Nobel price, once said that literature allows us to escape from the injustice of having just one life, of being just one person in the immense realm of existence; I am paraphrasing here. Masks give us the same opportunitie, allowing us to impersonate what we praise, fear, or disagree with; to appear as what we are not, or maybe as who we really are.

The dictionary traces back the etymology of the word

mask, to the Arabic

maskharah meaning Buffoon; it relates to the verb

sakhira “to ridicule”. In Spanish the word for mask:

mascara, which is certainly a direct adaptation from Arabic, could be literarily read as

más cara “more than the face” or “added face”, these could be understood as different levels of projections when one impersonates; one adds, enters a different plane of existence, being itself, the other, and a indefinable individual between the two. It is possible that this was the original purpose of the mask, as it is possible that it was for all the arts; the decontextualization of a concept (persona) to control it, to posses it, to gain power and reason over it, to have a better understanding of it. But this is not only valid for the shamanic ritualistic personifications, it is also for the act of the buffoon; ridicule something is to take it out of context, and to reveal with this isolation, the true nature of an issue, its “more that the face”.

In Mexico one can find masks anywhere, in markets, on the heroes of Lucha Libre, in the Zapatista Guerrilla, those mocking politicians, in museums and in folk dances. Masks in México can be traced back to the prehispanic period. Within the Aztec mythology, one of the four principal deities is Xipe-Totec “the flayed lord”; during the festivities to Xipe-Totec, the priest would flay a prisoner and then wear the skin as a representation of being reborn. Xipe-totec masks always present two levels of skin, one which is noticeable at the mouth; represents the deity wearing the skin of the other. There are also examples of prehispanic death masks divided in two, a skull and a living face; or with three concentric levels, from life to death, from a face to skull.

Later, with the Spaniards, came the European tradition of carnivals. First used to evangelize; the Spanish masks were adopted by the local population in a variety of syncretised festivities. Many Mexican towns or cities have this mixture of beliefs even in their denomination, where a Christian name combines with a local name; eg. Santiago Tianguistenco. It is within this cultural turmoil, that many masked dances were born; some of them as ways to praise a native deity while celebrating a saint; others to laugh at the European oppressors.

One of the best examples of these satiric dances is the one of the Chinelos, where european-like masks are worn in combination with extravagant clothing to represent the rich upper classes. It is said that this dance started when the native population of Tepoztlan began to make fun of the rich bourgeoisie celebrations.

Another example is “La Danza de los Manueles” originated in Tixtla. It is said that a governor of that province, Don Manuel, was an evil man, hateful and discriminative. The indigenous population presented as a birthday gift a dance wearing two different types of masks, one of an old man, and one of an old woman, representing Don Manuel and his wife. The governor was informed of the parody and instead of getting angry he requested that the dace be represented each year. It is possible to understand that indigenous populations not only see in those dances a way to celebrate, but also recognise on those masks the face of their ridicule oppressors.

Some years ago, it was common to see near traffic lights of Mexico City people selling latex masks of modern politicians, mainly presidents. It is relevant to recognize that there is an urge to make fun of politicians; one could find it in newspapers, in every talk, on internet and on masks. This “added face” which transforms us into our own oppressors, maybe to laugh at them, maybe to ask ourselves if we would act differently, if we are any different from the ones that torment us; maybe to posses them, to change their repressive acts into a smile, a smile that will grant us the mask of happiness.

Mexico is a country of masks, a country full of fear from revealing itself, fearful of being exposed to the outside; but the world is also a world of masks: Everyone is impersonating one or more different characters, protecting themselves from the hostile surroundings, from society, from the known tyranny of living just once. Vargas Llosa, the peruvian Nobel price, once said that literature allows us to escape from the injustice of having just one life, of being just one person in the immense realm of existence; I am paraphrasing here. Masks give us the same opportunitie, allowing us to impersonate what we praise, fear, or disagree with; to appear as what we are not, or maybe as who we really are.

Mexico is a country of masks, a country full of fear from revealing itself, fearful of being exposed to the outside; but the world is also a world of masks: Everyone is impersonating one or more different characters, protecting themselves from the hostile surroundings, from society, from the known tyranny of living just once. Vargas Llosa, the peruvian Nobel price, once said that literature allows us to escape from the injustice of having just one life, of being just one person in the immense realm of existence; I am paraphrasing here. Masks give us the same opportunitie, allowing us to impersonate what we praise, fear, or disagree with; to appear as what we are not, or maybe as who we really are.

The dictionary traces back the etymology of the word mask, to the Arabic maskharah meaning Buffoon; it relates to the verb sakhira “to ridicule”. In Spanish the word for mask: mascara, which is certainly a direct adaptation from Arabic, could be literarily read as más cara “more than the face” or “added face”, these could be understood as different levels of projections when one impersonates; one adds, enters a different plane of existence, being itself, the other, and a indefinable individual between the two. It is possible that this was the original purpose of the mask, as it is possible that it was for all the arts; the decontextualization of a concept (persona) to control it, to posses it, to gain power and reason over it, to have a better understanding of it. But this is not only valid for the shamanic ritualistic personifications, it is also for the act of the buffoon; ridicule something is to take it out of context, and to reveal with this isolation, the true nature of an issue, its “more that the face”.

The dictionary traces back the etymology of the word mask, to the Arabic maskharah meaning Buffoon; it relates to the verb sakhira “to ridicule”. In Spanish the word for mask: mascara, which is certainly a direct adaptation from Arabic, could be literarily read as más cara “more than the face” or “added face”, these could be understood as different levels of projections when one impersonates; one adds, enters a different plane of existence, being itself, the other, and a indefinable individual between the two. It is possible that this was the original purpose of the mask, as it is possible that it was for all the arts; the decontextualization of a concept (persona) to control it, to posses it, to gain power and reason over it, to have a better understanding of it. But this is not only valid for the shamanic ritualistic personifications, it is also for the act of the buffoon; ridicule something is to take it out of context, and to reveal with this isolation, the true nature of an issue, its “more that the face”.

In Mexico one can find masks anywhere, in markets, on the heroes of Lucha Libre, in the Zapatista Guerrilla, those mocking politicians, in museums and in folk dances. Masks in México can be traced back to the prehispanic period. Within the Aztec mythology, one of the four principal deities is Xipe-Totec “the flayed lord”; during the festivities to Xipe-Totec, the priest would flay a prisoner and then wear the skin as a representation of being reborn. Xipe-totec masks always present two levels of skin, one which is noticeable at the mouth; represents the deity wearing the skin of the other. There are also examples of prehispanic death masks divided in two, a skull and a living face; or with three concentric levels, from life to death, from a face to skull.

In Mexico one can find masks anywhere, in markets, on the heroes of Lucha Libre, in the Zapatista Guerrilla, those mocking politicians, in museums and in folk dances. Masks in México can be traced back to the prehispanic period. Within the Aztec mythology, one of the four principal deities is Xipe-Totec “the flayed lord”; during the festivities to Xipe-Totec, the priest would flay a prisoner and then wear the skin as a representation of being reborn. Xipe-totec masks always present two levels of skin, one which is noticeable at the mouth; represents the deity wearing the skin of the other. There are also examples of prehispanic death masks divided in two, a skull and a living face; or with three concentric levels, from life to death, from a face to skull.

Later, with the Spaniards, came the European tradition of carnivals. First used to evangelize; the Spanish masks were adopted by the local population in a variety of syncretised festivities. Many Mexican towns or cities have this mixture of beliefs even in their denomination, where a Christian name combines with a local name; eg. Santiago Tianguistenco. It is within this cultural turmoil, that many masked dances were born; some of them as ways to praise a native deity while celebrating a saint; others to laugh at the European oppressors.

Later, with the Spaniards, came the European tradition of carnivals. First used to evangelize; the Spanish masks were adopted by the local population in a variety of syncretised festivities. Many Mexican towns or cities have this mixture of beliefs even in their denomination, where a Christian name combines with a local name; eg. Santiago Tianguistenco. It is within this cultural turmoil, that many masked dances were born; some of them as ways to praise a native deity while celebrating a saint; others to laugh at the European oppressors.

One of the best examples of these satiric dances is the one of the Chinelos, where european-like masks are worn in combination with extravagant clothing to represent the rich upper classes. It is said that this dance started when the native population of Tepoztlan began to make fun of the rich bourgeoisie celebrations.

One of the best examples of these satiric dances is the one of the Chinelos, where european-like masks are worn in combination with extravagant clothing to represent the rich upper classes. It is said that this dance started when the native population of Tepoztlan began to make fun of the rich bourgeoisie celebrations.

Another example is “La Danza de los Manueles” originated in Tixtla. It is said that a governor of that province, Don Manuel, was an evil man, hateful and discriminative. The indigenous population presented as a birthday gift a dance wearing two different types of masks, one of an old man, and one of an old woman, representing Don Manuel and his wife. The governor was informed of the parody and instead of getting angry he requested that the dace be represented each year. It is possible to understand that indigenous populations not only see in those dances a way to celebrate, but also recognise on those masks the face of their ridicule oppressors.

Another example is “La Danza de los Manueles” originated in Tixtla. It is said that a governor of that province, Don Manuel, was an evil man, hateful and discriminative. The indigenous population presented as a birthday gift a dance wearing two different types of masks, one of an old man, and one of an old woman, representing Don Manuel and his wife. The governor was informed of the parody and instead of getting angry he requested that the dace be represented each year. It is possible to understand that indigenous populations not only see in those dances a way to celebrate, but also recognise on those masks the face of their ridicule oppressors.

Some years ago, it was common to see near traffic lights of Mexico City people selling latex masks of modern politicians, mainly presidents. It is relevant to recognize that there is an urge to make fun of politicians; one could find it in newspapers, in every talk, on internet and on masks. This “added face” which transforms us into our own oppressors, maybe to laugh at them, maybe to ask ourselves if we would act differently, if we are any different from the ones that torment us; maybe to posses them, to change their repressive acts into a smile, a smile that will grant us the mask of happiness.

Some years ago, it was common to see near traffic lights of Mexico City people selling latex masks of modern politicians, mainly presidents. It is relevant to recognize that there is an urge to make fun of politicians; one could find it in newspapers, in every talk, on internet and on masks. This “added face” which transforms us into our own oppressors, maybe to laugh at them, maybe to ask ourselves if we would act differently, if we are any different from the ones that torment us; maybe to posses them, to change their repressive acts into a smile, a smile that will grant us the mask of happiness.

Comments are closed.